Art Collection of August, Serena and Erich Lederer

Since February 2020 Facts & Files had been researching the art collection of August, Serena and Erich Lederer. The project is commissioned by Ralf von Jacobs, funded by German Lost Art Foundation. The first project was completed on January 31, 2021. The second started in June 2021, and was completed by July 31, 2022.

The provenance research project aimed to reconstruct the art collections of August, Serena and Erich Lederer. For this purpose, previous information, documents and archival records had to be reviewed, processed and analyzed in order to plan further research based on them. In addition, bank records and insurance documents in Switzerland, Germany and Austria were identified and evaluated, which could provide information on the Lederer collection before 1938. The persecution of the Lederer family starting in 1938, in particular the “Aryanization” of further assets such as shares and companies, had to be researched and described in more detail. It had to be checked if there were connections between the “Aryanizations” and the whereabouts of the art collections.

Another main event was the Gestapo looting in Vienna in March 1938, which is documented in a post-war restitution file. To determine information on this looting, the personnel involved in the house search and the exact chain of command were to be identified, and the looted artworks and objects had to be identified and their whereabouts researched. Therefore, the Gestapo officers involved in the house search in March 1938 had to be identified and their further activities documented, the few archival documents of the SD Vienna had to be consulted, and further archival records of the Gestapo had to be researched.

Additional to the archival research literature and catalogs raisonné were analyzed.

As a result, the provenance research project was able to identify 15 works of art from the Lederer Collection that were still present in 1939, but were not given back to Erich Lederer.

30 works of art could not be identified, because the description was vague and could not be verified by other sources.

Further research was conducted on works of art, which were taken by the Lederers to Hungary before 1938, in Hungarian archives.

Research Findings

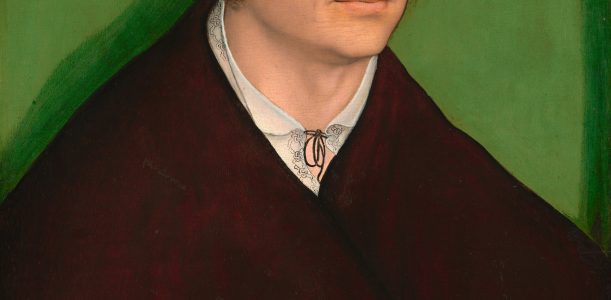

Serena Lederer was born in Budapest on May 20, 1867, the daughter of Simon Siegmund Pulitzer and his wife Charlotte, née Politzer. On June 5, 1892, Serena Pulitzer married August Lederer, an industrialist born in Böhmisch-Leipa on May 3, 1857. August Lederer was the managing director of the companies Raaber Spiritusfabrik AG and Jungbunzlauer Spiritus AG. August Lederer’s father, Ignaz Lederer (1820-1896), had already founded an alcohol refinery in Böhmisch-Leipa in 1859. He moved the refinery to Jungbunzlau in 1867, and introduced a new production process, that made it possible to produce better spirit from sugar beet molasses. His sons Richard, Julius, Emil and also August joined the company. Richard Lederer died unexpectedly in 1900, whereupon August Lederer took over the management, moved the headquarters of the company to Vienna in 1901 and bought additional factories.

August and Serena Lederer lived in Vienna, in Weidlingau Castle and in an apartment on the factory premises in Raab/Györ. On the initiative of Serena Lederer, the couple collected works of art by Egon Schiele, Gustav Klimt and other artists. They also collected works of the Renaissance. August and Serena Lederer are today considered the most important patrons of Gustav Klimt. Klimt’s Beethoven frieze, which they purchased, has immense symbolism in Austria to this day. The couple also acquired numerous drawings by Egon Schiele, who gave their son Erich drawing lessons.

After the “Anschluss” of Austria, Serena Lederer stayed mainly in Raab/Györ and Budapest since March 1938, having fled Vienna like her sons Erich and Fritz. Her daughter Elisabeth remained in Vienna. Elisabeth’s husband divorced her, and their young son died. Erich Lederer emigrated via Paris to Geneva.

The art collection of August and Serena Lederer has been the subject of research by Sophie Lillie. In her monograph on Gustav Klimt’s “Beethoven Frieze” and her dissertation, she investigated the collecting activities and the fate of the collection after 1938. There is no complete inventory of the Lederer collection, but several lists, which were made for different purposes at different times.

Renaissance and medieval works were acquired by August and Serena Lederer at auctions of the collections of Adalbert Freiherr von Lanna, Adolf von Beckerath, Emil Weinberger, Wilhelm Gumprecht, Heinrich Freiherr von Tucher, Augustin Gilbert, Camillo Castiglioni and Richard von Kaufmann.

The art historian Leo Planiscig (1887-1952), an expert on Renaissance sculpture who served as curator at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna from 1914 to 1938, published frequently on objects in the Lederer Collection. His research, as well as the publications of the art historian Bernard Berenson (1865-1959), provided an important basis for the identifications of Italian Renaissance works in the research project.

August Lederer died on April 30, 1936, and the art collection remained with his widow Serena.

The economic plundering of the Jewish population has probably not been researched in such detail for any country as for Austria. The Historical Commission of the Republic of Austria, established in 1998, investigated both the confiscation of assets and the restitution after the end of the war, which in Austria is called “restoring” (Rückstellung). Starting in 2003, the results were published, and by 2004 all 49 studies of the Historical Commission had been published. They can be found online completely here.

The analysis of the archival documents reveals a network of “old fighters”, who were member of the National Socialist Party and network before the takeover of the National Socialists in Germany in 1933. They became provisional administrators, trustees, etc., and administered and acquired assets of entrepreneurs who were Jewish by Nazi definition from 1938 onward. These persons were well educated, came from middle-class families, had participated in World War I as soldiers, and had joined the SA and the NSDAP at an early age.

Some of them, such as Otto Braun and the aforementioned Hermann Berchtold, were involved in murdering opponents after World War I. Because they were searched or convicted for the murder, they had to leave Germany, and went to Hungary or Spain. There they built up economic networks, which they were able to make very profitable from 1933, when the National Socialists became the German government. They were employed or commissioned by Germany to use their businesses abroad for the interests of the National Socialists. These structures were also evident in the administration and “Aryanization” of the Lederer family’s assets.

The Fascist “Arrow Cross” (Pfeilkreuzler) movement in Hungary was massively supported by National Socialist investments from 1933 onward. The research revealed that the Hungarian cooperative bank Hangya came under the influence of German National Socialists such as Otto Braun and acquired Jewish enterprises in Hungary like cold storage houses, forage factories and vinegar distilleries. Naturally, the Lederer Group, as the largest spirit manufacturer, came into the focus of these people. Hermann Berchtold, who was to become a trustee of the Lederer Group by 1938, was also active in this network in Hungary. Through the Hangya contact, he and Otto Braun became board members of the Austrian forest sales department as early as 1936, and of the forest owners’ cooperative in Austria from 1937. However, Hermann Berchtold could not personally attend meetings in Vienna because he was still searched for murder there in 1936. In Germany, meanwhile, he had been amnestied, and took an important post as SA leader in Stuttgart in 1933. Despite being imprisoned after the Röhm purge in 1934, Berchtold was employed in 1936 by a company called Transdanubia GmbH, and which he and Otto Braun had founded in Berlin. Transdanubia was linked to Hangya in a conglomerate of companies.

After the “Anschluss” of Austria in March 1938, Hermann Berchtold and Otto Braun became majority owners of the forest owners’ cooperative. Shortly thereafter, Hermann Berchtold became a trustee of the Lederer Group.

As a link between industry and agriculture, the Lederer concern and its ventures were important to the national economy. Spirit products were essential for armaments and warfare. The “Aryanization” of these companies was therefore of particular interest to the National Socialists.

A confidential report by the Vienna Foreign Exchange Office found that Hermann Berchtold and an involved banker named Adolf Boehm from Munich had violated foreign exchange regulations. Although the Foreign Exchange Office had originally investigated the Lederer family, these investigations were discontinued because nothing incriminating was found. In Hungary, meanwhile, an acquaintance of Hermann Berchtold and Otto Braun, Eugen Bogdanffy, had gained control of the Hungarian company Raaber Spiritus AG, which was expropriated on a hitherto unclear basis by the Hungarian state under Horthy.

Hermann Berchtold “aryanized” companies that belonged to the Lederer Group, apparently using straw men to acquire the companies for him. His high income as trustee and at the same time as managing director of the “aryanized” companies led to investigations by the Reich Ministry of Economics.

Hermann Berchtold went into hiding after the end of the war in 1945 and was prosecuted in Vienna. He allegedly lived in Zurich as Conrado Fernando Mayer and had Spanish citizenship, which he had acquired before 1933. His whereabouts and those of his wife Charlotte, née Krüger, remained unknown. His partner Otto Braun lived in Vienna after the war and ran an import-export business.

At the end of 1939, part of the art collection was in the possession of a shipping company as removal goods, another part had been confiscated by the Monuments Authority and placed in storage, other objects were housed in Weidlingau Palace, with Serena Lederer’s daughter, Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt, and in the Collegium Hungaricum in Vienna. No documents could be found on the looting of the Lederer Collection by the Gestapo in March 1938. The files on the Munich Gestapo man Franz Josef Huber, who was in charge of the “set-up” (Aufbauarbeit) of the Vienna Gestapo, contain no references to this, and no information was provided by the files from the Property Transaction Office (Vermögensverkehrsstelle). However, the looting of Maria Lederer’s house during the night of March 13-14, 1938, is documented by a report filed by Maria Lederer and various investigations. During this looting, NSDAP members confiscated jewelry from Maria Lederer’s apartment, which was subsequently forwarded to a certain “party comrade” Günther but did not turn up thereafter.

In his role as trustee, Berchtold wanted to sell the Lederer’s art collection to pay off the Lederer Group’s debts, which had been calculated after 1938. However, this did not happen, rather, some art objects were assigned to Adolf Hitler’s art museum in Linz “Sonderauftrag Linz“ and evaluated by the Special Representative for the Linz museum, Hans Posse. These objects are documented in the online edition of Posse’s travel diaries.

In the meantime, the Vienna Public Attorney’s Office had initiated investigations against the Lederer family for non-declaration of Jewish property. These criminal proceedings then focused on Serena Lederer, and also on the issue whether she was a Hungarian citizen or not. In 1942, the art collection in Austria was confiscated by the public prosecutor’s office but remained at the respective storage locations. Paintings by Gustav Klimt were stored at the shipping company Kirchner & Co. in Vienna, some of which were shown at the 1943 exhibition of the Vienna Secession, organized at the request of Baldur von Schirach. Other works of art from the Lederer Collection, including parts of the Beethoven Frieze and drawings, were lent for the exhibition by the Monuments Authority and the lawyer of Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt, Erich Führer.

On March 27, 1943, Serena Lederer died in Budapest. Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt was forced to the sell paintings from her parent’s collection to art dealers, and also two paintings by Gustav Klimt, Philosophy” and “Jurisprudence”, to the Austrian Gallery in Vienna (Österreichische Galerie).

In the spring of 1944, various works of art were moved to relocation sites; works of art from the removal goods remained with the forwarding company. Some objects ended up in Immendorf Castle, others in Thürnthal, in bank depots and in Bad Aussee. In July 1944, the shipping agency announced that the removal goods requested from them could unfortunately not be made available, as they had been bombed. On October 19, 1944, Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt died in Vienna after a long illness.

In May 1945, a fire was set in Immendorf Castle, where works of art were said to be destroyed.

Six objects had probably already been brought to Győr or Budapest by August Lederer, so they were spared from the various seizures.

One of these objects is a crystal relief depicting a woman, documented in the August and Serena Lederer Collection as being by the hand of Tullio Lombardi and acquired at the auction of the Wilhelm Gumbrechts Collection in 1918. This female bust was sold by a doctor named Tibor Jánossy from Budapest from the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest in 1979, where it still is part of the museum’s collection.

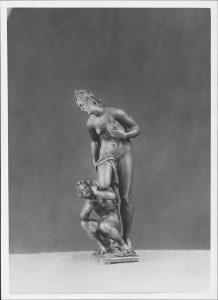

Two other sculptures by Bartolomeo Bellano and Benvenuto Cellini were also in Budapest before 1939 and remain untraced to this day. The bronze by Bellano depicts two men with a large bunch of grapes on their shoulders and probably came from the collection of Wilhelm Zatzka. The second sculpture was a bronze by Benvenuto Cellini, depicting Venus with Cupid. The Lederers had acquired it from the art dealer Jacques Seligmann in 1927.

At Serena Lederer’s request, the Hungarian embassy in Vienna and Berlin respectively had protested against the confiscation of the art collection and Weidlingau Palace to the German government in 1938.

Due to the interconnections of the Lederers’ companies located in Austria with companies in Hungary, the “trustee” Hermann Berchtold became active again in Hungary. In 1946, Hungarian newspapers reported that the Raab factory and also the Hazai liqueur factory actually belonged to the Lederers and that Eugen Bogdanffy together with Otto Braun had taken these companies under German influence. The influence of the German National Socialist government on the restructuring of the Hungarian economy was investigated by Margit Szöllösi-Janze in 1989.

The “1st Jewish Law” entitled “Law on the More Effective Securing of the Balance in Social and Economic Life,” enacted in May 1938, exempted persons who had converted before August 1, 1919, which probably applied to Serena Lederer. The law was announced by the Hungarian Prime Minister in Győr on March 5, 1938. This law defined “Jews” by religion, not by ancestry as in Nazi Germany. However, this was to change in Hungary after less than a year with the “2nd Jewish Law,” which adopted the National Socialist definition in 1939. Thus, Serena Lederer was also affected by this law in Hungary. On the local level numerous occupational and trade bans took place in Hungary, which have been little studied in research so far. In addition, as early as 1940, there were isolated deportations to Romania and murders when ransoms were not paid immediately. Efforts by the Hungarian embassy to have the seizure of the art collection lifted and Berchtold appointed as trustee ended in January 1942. In July 1943, there was still a communication from the Foreign Office to the Hungarian embassy in Berlin. Since 1941, there had been an agreement between the Hungarian and German governments that “Hungarian-Jewish assets in the Reich and the occupied territories would not be confiscated, but would be secured for the benefit of Hungary.” Considering this deal, the interventions of the Hungarians in Vienna and at the Reich Ministry of Economics cannot be characterized as altruistic. Three of the total of six objects located in Hungary remain missing.

After 1945, objects of the removal goods turned up with American military personnel. The works of art stored in Thürnthal and Bad Aussee were released in a settlement with Erich Lederer after lengthy proceedings with the bankruptcy trustees of the estates of August and Serena Lederer. Erich Lederer had to repay part of the debts of the estates with the proceeds from sales of artworks. To be allowed to export the artworks belonging to him from Austria, he needed permits from the Federal Monuments Authority. These were not granted to him at first. Instead, what happened more frequently in Austria took place: blackmailing. That meant that works of art were donated to Austria, in return for which their owners received export permits for other works of art. In 1949, paintings, watercolors and drawings thus became the property of Viennese museums and the Republic of Austria. These extorted “donations” corresponded to the wishes of the museum directors, which they had presented to the Federal Monuments Office. In addition, pre-emptive rights for Austria were demanded. It was not until 1950/1951 that Erich Lederer was able to dispose of and execute the rest of his family’s art collection.

Erich Lederer exported works of art to Switzerland in 1951. The American art historian and art dealer Harold Woodbury Parsons (1882-1967) helped him to sell the returned objects to American museums. Other important advisors to Erich Lederer were the art historian Wilhelm Suida (1877-1959), who was director of research at the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, and the art historian and art dealer Lili Fröhlich-Bum (1886-1981).

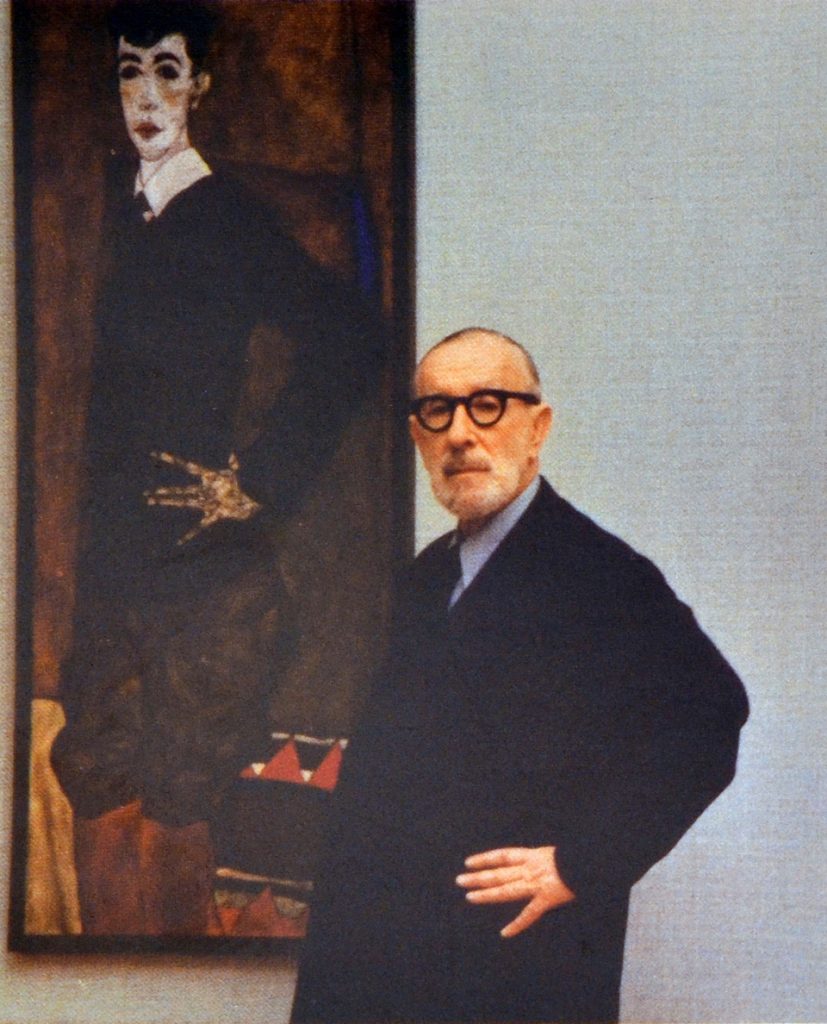

Erich Lederer supported research on Viennese Modernism with his expertise and Alice Strobl in compiling her catalog raisonné of Gustav Klimt’s works. Erich Lederer also acquired works of art himself, including works from the collection of Rudolf Leopold.

After his death, his widow Elisabeth donated 72 bronze sculptures and plaquettes to the Metropolitan Museum in New York.

Further donations followed to the Kunstmuseum Basel and to the Albertina in Vienna.

In 1999, 2000 and 2012, the works of art given as “donations” were restituted to the heirs of Erich Lederer, with the exception of the Beethoven Frieze.